|

|

||

|

by Alan Levenson PhD |

||

|

Alan Levenson's

study of Cleveland's Reform Congregation Brith Emeth

(1959-1986) and its rabbi, Philip Horowitz (1922-2002), began in 2007 when he was Professor of

History at the Siegal College of Judaic

Studies. In

November 2009 the Cleveland Jewish News published an

extract as

A Jewish Cleveland I never knew:

Congregation Brith Emeth. We

offered Dr Levenson an opportunity to

present a larger version of his essay on

this site, with links and more images. I

developed the text on this

page from his manuscript, with his review

and approval. |

|

Agents of Change:

Congregation Brith Emeth and Rabbi Philip

Horowitz This essay analyzes Congregation Brith Emeth (1959-1986), whose existence only lasted the tenure of its founding rabbi, and it analyzes the rabbinate of Philip Horowitz (1922-2002), who was not nationally renowned. To the rather obvious question: why bother to study this congregation/rabbi? there are three principal answers. Firstly, the family of the late Rabbi Horowitz insured that this congregation’s legacy would be preserved by cataloguing two major manuscript collections at Cleveland’s Western Reserve Historical Society. Thus, along with the interviews conducted by this author or by a research assistant, and the taped sermons of Rabbi Horowitz, the historian has a rich, yet manageable, body of evidence with which to reconstruct some unique features of this congregation. Secondly, there ought to be, in principle, some merit to studying a congregation/rabbi whose level of success falls within the normal rather than the extraordinary range. Finally, it is rare thing when participants in an institution a quarter-century defunct insist that their story be told. For the bottom line is that the former members of Congregation Brith Emeth (hereafter CBE) maintain that despite its short life, CBE exerted an enormous impact on hundreds of Jewish Clevelanders, many of whom have gone on to lead major agencies, win awards in Jewish education, become activists in the general community, and gone on to successful rabbinates in other cities. This project was generated, then, by a simple question. How did so much good come from the seemingly unexceptional? I will attempt to unravel this enigma in three stages by exploring: 1) the nature of the congregation 2) the nature of its central figure, Rabbi Philip Horowitz, and 3) the legacy of its participants, with a distinction between the experiences of the founding generation and that of their children. I. The Nature of the Congregation In Cleveland, the decade preceding the founding of Congregation Brith Emeth in 1959 followed the national pattern, when the national Jewish population was still growing and moving rapidly out of the city and into the suburbs. The already venerable and large Reform congregations - Anshe Chesed - Fairmount Temple (founded 1841) and (The Temple - Tifereth Israel (founded 1850) would be joined by two new smaller members of UAHC (now the URJ): Temple Emanu-El in 1947 and Suburban Temple in 1948. Congregation Brith Emeth, formed a decade after these two, reflected a further population shift east, from the inner-suburbs (the three "Heights" of Greater Cleveland) to the outer suburbs. Although for the first five years of its existence Brith Emeth met weekly at the First Unitarian Church and for the High Holy Days at Byron Junior High School, both on Shaker Boulevard in Shaker Heights, it built what it hoped would be its permanent home more than two miles east in Pepper Pike, Ohio, a fashionable Cleveland exurb. The population of Jewish Cleveland was still on the rise, and even lightly affiliated Jews belonged to synagogues and spent their charitable dollars establishing Jewish institutions. Brith Emeth had members who were lawyers, doctors, and business owners, but also blue-collar Jews and Jews of modest means. Considering its demise, mainly the result of financial stresses, it probably had too few wealthy benefactors on its membership rolls. One last factor helps place CBE among Reform congregations formed in that golden era. Michael Meyer has identified the phenomenon perfectly: CBE had none of the German-Jewish versus Russian-Jewish tensions of older Reform congregations for the simple reason that its founding members were mainly second and third generation descendants of Eastern European Jews. Moreover, in a frankly oligarchic Jewish city, where multi-generational membership and deep pockets count for much, CBE took a decidedly democratic approach as to congregational governance. The meeting for the creation of a possible new Reform congregation took place on April 30, 1959 at Richmond Elementary School. According to Dr. Jane Avner, the original processor of this archive at the WRHS, eight families had already taken the initiative to encourage Rabbi Horowitz to explore the viability of a new congregation. Since it was locally and nationally recognized that existing Reform congregations in Cleveland had reached their membership capacities, the overwhelming response was not so surprising in retrospect. Nevertheless, Rabbi Horowitz’s daughter, Ilana Ratner, remembers vividly her father’s excitement when he returned home after the meeting and reported the large turnout. The name Brith Emeth (in English "Covenant of Truth") was chosen by Horowitz and congregational president Martin Friedman. By Rosh Hashanah of 1959, Congregation Brith Emeth had 300 member families. This would rise to at least 435 families by the mid-1960s. At Rosh Hashanah 1960, Horowitz could claim 500 students enrolled in the religious school. The early years had an informal feel to them, more like a havura than the staid Reform Temples of the early 1960s that one conjures up in one’s mind. By the early 1960s, CBE decided to build a permanent home and enlisted the services of the world-famous architect Edward Durell Stone, designer of the New York Civic Center, the United States Embassy building in New Delhi, and the Huntington Hartford Museum in Lincoln Center According to Clevelander Sheldon Gross, an architect, Stone’s initial response was that CBE could not afford his services. After some cajoling, Stone agreed to help with design, but have locals, including Gross, also a CBE activist, supervise the actual planning. This too turned out to be complicated, since the Pepper Pike City Council was none too eager have a Jewish house of worship in its domain. Several years earlier, Fairmount Temple had won a zoning war with the city of Beachwood. Now, Brith Emeth would also emerge victorious over an opposition animated in part by anti-Semitism.

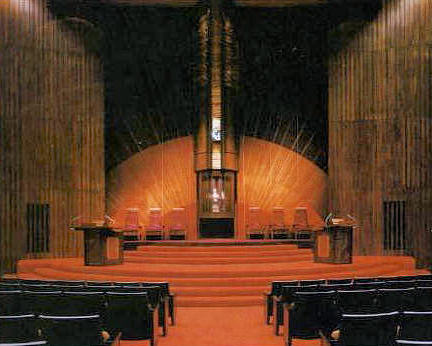

The Temple-in-the Round, as it was known, was built in 1967 at an estimated cost of $1,250,000. Years later, the building remains a source of intense controversy among congregants. While the official minutes at the time reflect congregational pride in the structure, and the modernist nature of the building set well with Horowitz’s highly aesthetic-artistic sensibility, many former members looked back at this undertaking as a disastrous "edifice complex." In fact, the building was too expensive for the 500-family congregation to support. Its completion and upkeep continued to be problematic throughout the 1970s and up until the congregation’s demise; largely, though not exclusively, the product of financial pressures. CBE had debts of $600,000 when it closed in 1986. By that time, Rabbi Horowitz had re-married into a wealthy family (his first wife Sophie had died in 1980 of ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease). He had led Brith Emeth for twenty five years, including several years of institutional and personal stress, and through at least one difficult associate rabbinical relationship. The last-ditch effort to save the CBE was a proposed merger with Temple Emanu-El. Although CBE had an impressive building and was farther to the east, it had fewer members (approximately 500 versus 800) and was in a less favorable financial situation. Emanuel-El’s President, Jerry Schleifer, gave the pros and cons of the proposed merger with CBE. He spoke in favor, but the conditions reflected very clearly which congregation would be the senior partner, and specified that their rabbi, Daniel Roberts, a generation younger than Horowitz, would be "Head Rabbi," while Horowitz would take the title of Rabbi Emeritus. Although the exact sequence of events is unclear, the merger failed. Brith Emeth was acquired by Park Synagogue, a large Conservative congregation. Although there was some attempt to grant havura status to former CBE members, along with a three-year grace period of paying dues at CBE’s lower rates, this does not seem to have yielded many results. Some CBE congregants stayed at Park Synagogue, others followed their children’s (or children’s spouses’) choice of congregation, and some disaffiliated altogether. After seventeen years, the CBE experience was over. |

|

II Rabbi

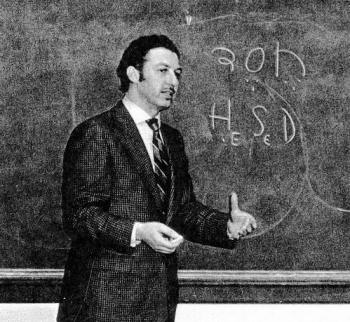

Philip Horowitz (1922 - 2002) Thus far, I have not said much about the central character of this story, Rabbi Phillip Horowitz. Born "Pinchas" in Vienna, in 1922, he grew up in New York, and was the product of a childhood that was both traditional and iconoclastic. Horowitz received his first two degrees from Yeshiva University Teachers College (Teachers Certificate in 1939, B.A. 1942), and Columbia University (M.A. in 1945). Rav Joseph Soloveitchick was already teaching at Yeshiva during Horowitz’s stay and he was quite taken with this giant of scholarship. Nevertheless, Horowitz made the unusual – and as yet inexplicable — decision to study at the Jewish Institute of Religion (JIR) in New York, where he received ordination after only two years (1951). The JIR, located in the heart of Manhattan, had been founded in 1922 by Rabbi Stephen Wise, at that time America’s most famous rabbi. Although Wise was Reform, most of his faculty members were not, and the overall Jewish atmosphere at JIR certainly differed from Hebrew Union College (HUC) in Cincinnati, founded by Isaac Mayer Wise back in 1875 and led by the anti-Zionist Julian Morgenstern until his retirement in 1947. Although Wise could not attract a permanent faculty – hard to do without adequate funds – some famous figures in American Jewry taught there. By the time Horowitz graduated, the JIR had combined with HUC. Before founding Brith Emeth, Rabbi Horowitz served as educational director for Forest Hills Jewish Center in Queens, New York and as Associate Rabbi and Religious School Director at Anshe Chesed - Fairmount Temple in Cleveland from 1952-1959. Fairmount Temple, though classical Reform in its liturgy, also enjoyed a long tradition of distinguished Hebraists in its employ, particularly in its religious school. Horowitz probably found more like-minded thinkers among his fellow-educators than his congregants. On Yom Kippur in 1955 he sermonized as follows:

Whether Jews in the 1950s wanted to hear that their own Jewish education needed improving may be doubted, but at CBE Horowitz had the opportunity to test his views. In any event, following the tragic death in an auto accident in Spain of the venerated Rabbi Barnett Brickner, who had served the congregation for 33 years, Fairmount Temple gave the top job to Arthur Lelyveld, then head of national Hillel and active in the American Jewish Congress. Lelyveld went on to a distinguished rabbinate, providing American Jewry with an iconic civil right image just behind Abraham Joshua Herschel’s marching arm in arm with Martin Luther King. On a voter registration march, Lelyveld had his head staved in by some toughs. The picture, in all major newspapers, made him a national figure of courage. And indeed, that kind of image, that kind of rabbi, was what a progressive Reform congregation wanted. Horowitz was, as we shall see, quite interested in civil rights. But his passion was educating Jewish children – always a less noteworthy and remunerative task. Probably, Lelyveld’s national orientation and reputation was not the whole reason he got the nod for Fairmount’s top post. Horowitz had served Fairmount for seven years, long enough to acquire enemies as well as admirers, and the phenomenon known as "no prophet in his/her own city" operates very effectively in rabbinic hires as well. Like most of liberal rabbis of that era, Horowitz was involved in interfaith dialogues. In 1964 Rav Joseph Soloveitchick, a former teacher of Horowitz’s at Yeshiva College, published "Confrontation," an influential call for Orthodox rabbis to be very circumspect in any such endeavors. Soloveitchick’s essay had a chilling effect within the ranks of Orthodox Rabbis. This issue was a clear dividing line between Orthodoxy and Liberalism in that era, and there is zero doubt as to where Horowitz stood. He spoke at many churches and schools and was honored by Shaker Heights High by giving the commencement benediction, the same year one of his three daughters graduated. He received letters asking about his views on Church–State relations from school officials, ministers and other rabbis. Horowitz had an interesting career – I do not know how typical of that era. There were several trips to Israel, a visit to Russia and teaching Judaism in Poland. He corresponded with some notable figures in the Jewish world including Maurice Eisendrath (1902-1973), Jacob Raeder Marcus and Lily Montague. Horowitz also led Farm Worker Sabbaths, visited Jewish prisoners in the Chillicothe, Ohio jail (and received some moving thank-you notes for doing so), and would weigh-in on a flurry of local controversies from the pulpit. Summers were time off, often spent at Camp Kutz, where Horowitz served as rabbi-in-residence. Terry Pollack, a teacher at Shaker Heights High, television personality, and former director of the ADL’s "World of Difference" program, also led the CBE youth group and taught in the CBE religious school in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He remembers how Horowitz would mesmerize campers with stories from the Hasidic masters and of his struggles at Americanization. Horowitz also taught at local colleges, including John Carroll University, which has a long-standing tradition of offering classes in Judaic studies. He was Visiting Professor of Theology 1968-1978, and must have taught hundreds of JCU’s predominantly Catholic population.

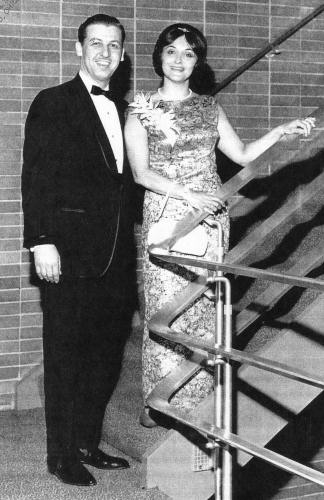

The Brith Emeth kids were encouraged, and sometimes forced, to do Jewish summer camping, even if the camp was Zionist Hebrew-speaking Camp Massad Bet. Many of these children went on to become rabbis and cantors and educators in Cleveland and beyond. Horowitz was a confirmed Zionist, which by the 1960s had become the majority perspective within Reform, but I do not know of any other Reform rabbi of that era from Cleveland other than the renowned Abba Hillel Silver, who considered Aliyah, in Silver’s case as semi-retirement spot. But Horowitz had in the 1950s, when he worked with Eisendrath to develop a program of Progressive Judaism in Israel. His visit in 1956 stuck with him a long-time, and in sermons, Horowitz would often draw on metaphors from his experiences there. No other rabbi, as Horowitz bragged to Eisendrath and the UAHC scholarship board, sent so many of his students to summer and semester-length Israel programs. His rabbinic discretionary fund seems to have been largely devoted to sponsoring just such trips for CBE children whose parents could not afford them. Horowitz certainly had a global view of the Jewish condition and lobbied on behalf of Soviet Jewry, the "Jews of Silence." Although it seems hard to believe today, American Jews needed plenty of cajoling to aggressively demand freedom for this oppressed Jewry, most particularly the right to emigrate. The Cleveland campaign for freeing Soviet Jewry was a grass-roots initiative started by some NASA scientists on Cleveland’s West Side, the wrong end of town from a Jewish perspective. Horowitz seems to have been the only rabbi to be an initial signatory on what became a slew of publications calling the oppression of Soviet Jews to the attention of the Cleveland Jewish Federation, and ultimately to national prominence. Their activism on Soviet Jewry’s behalf began in the early 1960s and plenty of Horowitz’s Friday night sermons in these years were devoted to publicizing this cause. "Silence on the Soviets" (December 15, 1963) was vintage Horowitz — the 14-page sermon was part legal brief, part call to action. Like his stand on unilateral disarmament, his extreme anti-John Birch and anti-HUAC/anti-McCarthy jeremiads, I suspect some of his congregants must have found Horowitz too political. Rosh Hashanah sermon 1965 — Civil Rights; Rosh Hashanah sermon 1968 — Vietnam; most years, Horowitz used his High Holy Day sermons to address the questions of the day. Like all of his sermons, including the October 17,1969 "Is the Negro Equal?" the aforementioned show Horowitz a careful student of the issue, usually marshaling statistical evidence, historical context and traditional Jewish sources. This seems almost to have been the typical Horowitz pattern, although I have no indication that he thought of it as a sermonic "formula." At the end of the day, though, Horowitz was a "stay at home rabbi" whose magic was performed within the circular walls of the Temple in the Round. Horowitz gave a lot and demanded a lot. He enjoyed his bima and sometimes spoke at too great a length (what good rabbi doesn’t), but commanded enormous loyalty from his congregants. His first wife, Sophie Horowitz, was not a Type-A rebbetzin. Their marriage, between a comfortable German Jew (Phil) and a poor Russian Jew (Sophie), was what was once considered an intermarriage in Jewish circles. Gracious and beautiful, she stayed largely in the background, despite being active in the Sisterhood and despite the proto-feminist character of the religious school (the couple, after all, had three daughters and no sons).

A rabbi once told me that there were ‘cat rabbis’ and ‘dog rabbis’ – the quiet introspective listeners, and the boisterous, know everybody by first-name talkers. In public, at least, Horowitz fell into the latter category, and most congregants remember a leader who always had a quip, a word of greeting, or a joke readily at hand. But those closest to Horowitz remember an introspective man who liked his "quiet time." Still others remember a rabbi with pastoral abilities – not always the case in rabbis who came up in the 1940s-1950s, who rarely received formal training in counseling, although, increasingly in this era, congregants leaned upon the rabbi for such services. Horowitz put his early immersion in Jewish sources to good use. We possess letters in his hand in both Yiddish and Hebrew, though the language of his boyhood home was probably a Yiddish-inflected German. His sermons and letters display profound learning and are often crabbed with biblical and rabbinic phrases in his own hand, usually deployed with an interesting twist. He studied traditional sources regularly, often by himself, and then, later in his career, with Rabbi Stanley Schachter, Rabbi Emeritus of the large Conservative Synagogue, B’nai Jeshurun. As Schachter recounted, he and Horowitz shared an enjoyment both of the minute analysis of the argument "yeshiva-style learning" combined with sudden lurches into grand areas of theology, psychology, and religion. Early in his career, Horowitz officiated at intermarriages, but as he became more displeased with results (plenty of marital strife and plenty of broken promises about raising children Jewish), he stopped doing so. In 1965 Horowitz was still delivering sermons stressing the importance of both halves of an intermarriage attending "choosing Judaism" classes. By the late 1970s we have letters from Horowitz politely, but firmly explaining that he did not conduct intermarriage. In this changed attitude, Horowitz was not alone. The Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Reform rabbinical assembly, debated intermarriage and came down in 1973 with statement discouraging, though not banning, the practice. His letters to and from Jacob Raeder Marcus, the founder of American Jewish historiography as a serious discipline, are side-splitting funny, as each man tried to out-do the other in a melitzah—the practice of writing a letter by stringing together citations from Bible and rabbinic literature. Given his traditional upbringing and the growing willingness of Reform congregations to experiment with ritual, it comes as no surprise that Horowitz proposed a Reform Shulchan Arukh, law-code, in a Yom Kippur sermon. The sermon, by the way, provides a good indication of why some interviewees felt that Horowitz spoke above their heads—the sermon runs eighteen pages, involves statistical evidence, presumes a thorough knowledge of Jewish history and sources, and culminates in the following tripartite acronym, presumably echoing the three-fold division of Tanakh (The Shulchan Arukh is organized into four principal parts):

Horowitz was fond of coining these acronyms and also of coining gematriyah, the playful assignation of meaning based on the numerical value assigned every Hebrew letter and word. I do not know if his congregants enjoyed these displays or were simply baffled by them, but most of my interviewees expressed pride in having a learned rabbi, who they characterized, somewhat unfairly on this point, as "not really Reform." (The Silvers father and son were both very capable Judaic scholars by any measure – I am less familiar with the Jewish learning of other Cleveland rabbis of that era.) Reading Rabbi Horowitz’s sermons was a good reminder that even golden eras have ominous clouds. The specter of nuclear annihilation was fading by the end of Rabbi Horowitz’s tenure, but the core of it took place during era of under-the-desk nuclear drills, an exercise presumably making it easier for surviving, irradiated janitors to sweep up human remains. Horowitz proposed unilateral disarmament, which must have been unpopular with his congregants and Cleveland Jewry, but he argued it just the same. In an undated Yom Kippur sermon, Horowitz took the Book of Jonah to press his case for world peace. The sermon ends on a note that combined the Reform Mission ideology with a call for activism:

Civil rights was, sometimes literally, a burning issue, and though he did not bear bloody bandages on his head as did Arthur Lelyveld, or march with Dr. King as did A. J. Heschel, Horowitz spoke forthrightly about equal rights for Negroes and CBE adopted a lengthy statement supporting equal treatment in the workplace, entitled "Importance of religion in Everyday Life: Program for Racial Justice." Last years are usually tough, and Horowitz’s were no exception. Sophie died of ALS in 1980 and congregants remember a more withdrawn man afterwards – the rabbinic adage that a death always affects the spouse the most: "a man is not dead except to his wife" ("ayn ish met eleh l’ishto") seems to have been true in this case. Horowitz retired from Brith Emeth to watch it disappear, suffered a stroke, and eventually died in 2002. Despite this, he enjoyed a second happy marriage, this time to Ruth Miller, conducted many of the simhas of his Brith Emeth graduates, and watched them go on and impart the passion he so manifestly possessed. |

|

III. The Legacy Rabbi Horowitz probably did not see himself as a CEO of Brith Emeth, nor do I think that the current corporate model of congregational leadership would have appealed to him much. But it is noteworthy that Horowitz had a talented and active supporting cast. Unlike some other Cleveland congregations I have either seen or heard about, CBE did not feel like a one man show. In its brief history, CBE had enjoyed a number of associated rabbis, a popular Cantor Sanford Koblentz. CBE also had committed educators and educational directors, and an administrator, Elaine Conant, who, not surprisingly, helped keep all the balls in the air. The professional leadership at CBE was matched by a highly active lay leadership. The synagogue board had the usual numbers of big egos and big givers, but the level of adult activism and engagement seems to have been high, even for the golden era. "Brith Emeth was like family" was the quote that appeared verbatim in nearly all my interviews, as well as written record. The Brith Emeth team included exceptional religious school directors (Morris Sorin who went on to become first head of Agnon School and Seymour Friedman who became Cleveland Schools Superintendent), and unusually committed Jewish educators (Helen Samuels, Terry Pollack). Apparently, the Purim Carnivals were legendary, sort of the equivalent of contemporary Cleveland ’s kosher rib burn-off. There was constant innovation in the religious schools: plays, dramas, new tunes. "Make your Judaism" was another quote the alumni repeated as if they had been fed talking points. One member recalled the antiphonal singing of "u’vchen tzadilkim," a High Holy Day Prayer, as something he looked forward to all year even though he never liked worship services — before or since Brith Emeth. I was struck by the fact that many Brith Emeth families made CBE their second home. There was Brotherhood, Sisterhood, Couples Club, PTA, home study, Torah study, social action committees, ritual committees, and a bi-weekly news bulletin The Covenant. One could spend most of the week outside of work and home at a congregational activity, and many of the members did. Not unusual for the interviewees to tick off the number of days in a week they would spend at CBE as follows: Friday night services, Tuesday night bingo, home-based Torah study, Brotherhood/Sisterhood Thursdays; Sunday bowling league after dropping the kids off at Sunday school. The drop and drive phenomenon has been excoriated by students of Jewish life for decades, including by Cleveland’s Rabbi Daniel Jeremy Silver, who called on Reform Jews to be more religiously committed and less satisfied with a "theological smorgasbord." Historian Edward Shapiro, who cited Silver’s critique, agreed, "It is doubtful that largely irreligious Reform laity would respond to Silver’s call for a renewal of "religious obligation." For them the appeal of Reform was institutional rather than theological or ideological. They might have hungered for community, but there was no indication that they were prepared for a life of spiritual commitment and discipline. In this respect, they were typical of American Jewry, for whom being Jewish was a matter of identifying experientially with the Jewish people and not of observing ritual or Jewish tradition." But it seems to me that in the case of CBE, this Sunday morning ritual served a highly functional division. The "founders" were not so pious, just hard-working adults needed to socialize and relax; moreover, Jews who found a place they could commit to enjoyably. They were not bowling alone, but as a community, even as their children were experiencing something very, very different. For their children, matters stood differently. The very first Religious School statement of objectives (1959-1960) summarized the ideology of CBE in its last plank: "V. To make the child a functioning Jew. Thru familiarity with Jewish home ceremonies. Prayers he can use. Songs." The Sunday/Hebrew schools achieved a great deal with Hebrew language, understanding prayers, learning the Hebrew songs, achieving ritual competence far beyond what would have been considered the norm for Reform congregations in that era. The preferred term at Congregation Brith Emeth was Ben Torah or Bat Torah – a term some interviewees disliked for being unusual. But Horowitz had a rationale: for him, it was an acknowledgment both of the non-halachic nature of the congregation (after all, his congregants did not intend to live by as many of the 613 Commandments as possible), and also that the age of thirteen marked the beginning of the learning process. At CBE this seems to have been approximately true: their teens went on Israel study trips, participated in Torah corps and junior choir, attended Jewish summer camp and flocked to NELFTY (North Eastern Lakes Region of Temple Youth). Youth activism was the norm, not the exception. It was also the congregation’s greatest pride:

I am not sure if the members of Brith Emeth would agree with my analysis, but it seems that while it was a family-friendly congregation to the highest degree, the "founders" and the "children" got something very different from their experiences. The founders found an accepting society, whatever one’s economic class, social status or even personal observance. (One family told me they always kept kosher, but never received any quizzical or hostile responses.) The comment "not quite Reform" popped up in conversation often, no doubt partly a product of Horowitz’s traditional background, and arguably, an anticipation of the trans-denominational openness typical of so many congregations today. The founders also found a social world, probably encouraged by the relatively small size, economic egalitarianism, and newness of the congregation. Even on Sundays, they were not "bowling alone" as a recent book on American society puts it; they bowled together. They appreciated Horowitz’s learning even if they did not always understand him, and found the ritual participation of their children thrilling. The children received something we most often associate today with students at Jewish day-schools: ritual competence and confidence and unambiguous Jewish identity, matched with a love of Hebrew and an ability to experience Judaism as celebration. The religious school valued creativity and an attitude Leonard Fein captured in his book titled Reform is a Verb. The children were not indifferent to the social benefits either: several interviewees admitted that in regional or national youth conferences they felt themselves better educated and better prepared than most of their Reform peers. (A surprising number of second-generation interviewees remembered that their siblings were all involved.) Whether this generational analysis is as sharp as I am suggesting, this much is certain: after nearly two decades as participants in a successful congregation, very few CBE graduates have ever found that magic again, and many have not been able to provide that magic for their children They may be active Jews (and most seem to be affiliated ones), or even Jewish leaders, but they have not been able to replicate their experiences in the 1960s -1980s at Congregation Brith Emeth. Lauren Rock, President of Montefiore, Cleveland’s nationally known Jewish senior center, and an active member of the Jewish community, summarized the sentiment uttered by many regarding subsequent affiliations: "It never quite feels like your home." |

|

IV. Three

Concluding Historiographical

Observations

Brith Emeth did not think of itself as a Reform congregation as much as a Liberal one. A number of our interviewees kept kosher, Rabbi Horowitz donned his kipa, and although there was a Confirmation that was taken seriously, so too were the Ben/Bat Torah Services. I did not find any Horowitz sermon which took a partisan Reform point of view, although there were many which took an aggressively communalist (klal Yisrael) perspective. This era was different from the one described by Jeffrey Gurock in his seminal article on rabbis who traveled between Orthodox and Conservative congregations in the first decades of the twentieth century, but the description "trans-denominational" seems to apply to CBE. As Horowitz sermonized on Rosh Hashanah 1960:

The Popular Impression of ‘Classical Reform’ Staidness Contrary to the popular impression of American Reform Judaism after the end of the heroic era of Classical Reform, the post-World War II years were not a spiritual wasteland in which long-winded rabbis sermonized to empty pews. Michael Meyer, among others, has shown the considerable ferment in these years. Brith Emeth demonstrates it in exactly the areas Meyer mentions: liturgy, early childhood education, and a greater willingness to experiment with ritual. CBE did not produce theologians, but it did produce rabbis and cantors and a generation of unusually committed young Jews, who participated in Jewish life in Cleveland and beyond. Perhaps the CBE experience will provide one more counter-example to this outworn (often polemically invoked) caricature of Reform Judaism in the 1960s-1980s. Failure or Success? Was Congregation Brith Emeth a failure or a success? The reader will long since have realized my verdict, and possibly come to his or her own. Nevertheless, the limitations of CBE deserve an airing. The congregation lasted but one rabbinic tenure, and that in a city with a Jewish population that had been relatively stable, though, by the 1980s, aging. One consequence was that dozens of Jews highly active in a congregation, principally the founders’ generation, returned to the back pews, or simply returned to being dues-paying, affiliated but uninterested congregants. To have let slip what had been so assiduously cultivated over the congregation’s twenty five year history cannot be written off as a matter of little consequence. Nevertheless, I think the legacy of CBE must be judged a

success; the children who went on to do notable things in the Jewish and

general community, exceeded what might reasonably have been expected for a

congregation of that size. I cannot think of a way to quantify this, but the

anecdotal evidence from congregants and non-congregants in Cleveland seems

overwhelming. But I am sobered by the thought that had this material not

been called to my attention, quite coincidentally at that, it is unlikely

that anyone else would have taken up this tale. ● |