|

|

|

|

|

Renowned Sculptor and Creator of Cleveland Lincoln at

Gettysburg Statue

GAIL GREENBERG |

||

|

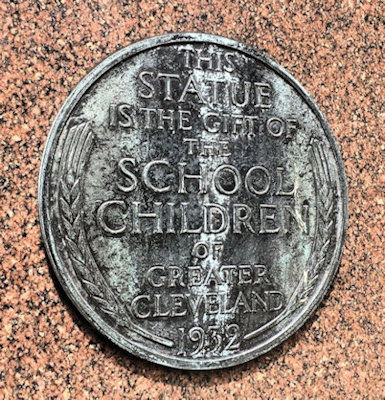

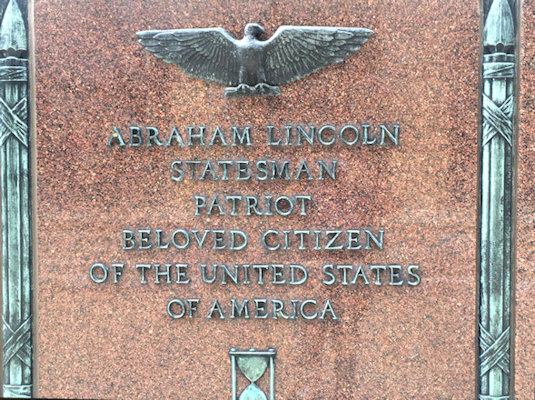

Max Kalish (March 1, 1891 to March 18, 1945), a graduate of the

Cleveland School of Art and an internationally-acclaimed sculptor,

created the statue of Abraham Lincoln that was purchased for the

city with the pennies of Cleveland school children. The statue,

which includes the Gettysburg Address at its base, faces west on

Cleveland’s Mall, in the building that was formerly the Cleveland

Board of Education and is now the Drury Plaza Hotel.

Kalish was married to Alice Neuman on November 20, 1927. The couple had two children, Richard and James, who were both born in Cleveland. Kalish died in New York City and was buried in Cleveland’s Mayfield Cemetery. Rabbi Barnett R. Brickner of Euclid Avenue Temple (Anshe Chesed) conducted the service. Career Highlights and Timeline Max Kalish was born Max Kalichik in Wolozyn, Lithuania to Joel and Hannah (Levinson) Kalichik. The family immigrated to Cleveland in 1896 where Kalish was given an Orthodox Jewish education. As a boy, he began to show signs of artistic talent in drawing. Although a professional artist was an unknown pursuit in his family’s scholarly background, Kalish’s marked ability finally won over his parents’ hesitation. At age 15, he won a scholarship to the Cleveland School of Art, graduating in 1910, when he was 19, and winning first prize for life modeling. One of his first post-graduate works in clay was an original conception of Judas Maccabeus that won Kalish national recognition. A copy of this piece was purchased by Rabbi Louis Wolsey, the first American-born and trained rabbi to serve Anshe Chesed Congregation. |

||

|

||

|

In 1910, Kalish studied at the National Academy of Design in New York City. His roommate was the famous painter Alexander Warshawksy. (Warshawsky, whose family emigrated from Poland, came to Cleveland from Sharon, PA, also attended the Cleveland Institute of Art.) Two years later, Kalish went to Europe to study at the Academie Colorossi and then the Academie des Beaux Arts. He exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1913. Returning to the U.S. in 1913, he was invited to join the sculptural staff of the Pan-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. This was the first in a long list of honors he was awarded, among them a lectureship at the Cleveland School of Art, associateship in the National Academy, and memberships in the National Sculpture Society and the Allied Artists of America. Back in Cleveland that same year, he tried and abandoned his dental school aspirations, yet gained a mastery of body structure. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916 and for the next three years helped design prosthetics for wounded soldiers. At the same time, Kalish modeled a series of one-third life-size portrait figures of soldiers and military officers. He was honorably discharged from the service in 1919. Beginning in 1920 and for the next 12 years, he divided his time between Paris and Cleveland. In 1932, he moved to New York and maintained a studio there for the rest of his life. From 1920 to 1937, Kalish created about sixty of these figures of American laborers, for which he earned wide recognition. Among these figures were a locomotive engineer and a newspaper printer. His study of a breadline in 1932, depicting a hobo, a mother and child, a war veteran, and a dope addict spurred both great admiration as well as controversy. Kalish also created many works of Jewish interest including the Baruch Spinoza Memorial plaque in the Hebrew Cultural Garden. The Cleveland statue of Lincoln at Gettysburg Perhaps, though, Max Kalish is best known in Cleveland for his Abraham Lincoln statue, financed by more than $30,000, raised by the city’s school children. The great bronze figure took several years to complete and was unveiled here on Lincoln’s birthday in 1932. Lincoln visited Cleveland only twice – once in life and once in death. That first visit occurred on February 15, 1861, when Lincoln was on his way from Illinois to his inauguration in Washington D.C. Excited crowds gathered at the Weddell House on the corner of Bank Street (West Sixth) and Superior Avenue to hear Lincoln speak from the balcony. Four years later, on April 28, 1865, the slain president’s funeral train arrived in Cleveland. The casket was then drawn by horse and carriage to Monument Park (Public Square), followed by a procession of dignitaries and veterans. Thousands of Cleveland area residents gathered in the rain to file past the open casket. In 1923, Lincoln was again in the Cleveland news, as plans for a local memorial were debated. Controversy arose over the choice of sculptor and the location of the statue. Ultimately, Max Kalish was chosen as the sculptor. The originally proposed site was to have been at the intersection of Huron Road and Euclid Avenue in Playhouse Square. After much debate, however, the statue ended up on the eastern side of Mall A, at the main approach to the new Cleveland School Administration Building. The new Kalish Lincoln statue revealed the Emancipator as he delivered his immortal Gettysburg Address at the statue’s dedication and unveiling on the afternoon of February 12, the 123rd anniversary of Lincoln’s birth. Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver chaired the ceremony which was held at the Public Music Hall. The event and celebration climaxed a movement inaugurated by Rabbi Silver about nine years earlier, which resulted in the formation of a Lincoln Memorial Commission and a fund drive in which Cleveland’s school children accumulated their pennies. Because of the children’s role in this civic undertaking, they were given preference in the day’s ceremonies. More than 2,500 children attended the dedication program, when the statue was formally presented to the city and the Cleveland schools by Rabbi Silver, who represented the Lincoln Commission. Sculptor Max Kalish was introduced to the gathering. The program opened with music by the Glenville High School Band. A film depicting the life of Lincoln was shown, and Rev. Joel B. Hayden gave an address which was broadcast on radio station WTAM. Russell V. Morgan, director of music in the schools, lead the singing of “America.” Following the presentation address by Rabbi Silver, the statue was accepted by Board of Education President E.M. Williams and Acting Mayor Harold H. Burton. Kalish said he had endeavored to represent Lincoln in the act of delivering his immortal address at Gettysburg. The sculptor wanted to give a glimpse of the soul of the great man as he consecrated himself to carry on the cause for which the soldiers had died. After the program in the Public Music Hall, the children marched to the section of the Mall, where they were among thousands of persons who witnessed the statue’s unveiling. Miss Helen Green, a descendant of James Lincoln, cousin of President Lincoln, pulled the strings that released two American flags that draped the statue. Epilogue In 1935, the Kalishes moved to Great Neck, Long Island, and until the invasion of France, spent much of their time in Paris. His passionate drive at his work is said to have taken a toll on Kalish’s physical strength. After an illness of several weeks, he failed to rally from an operation. He died at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York on March 18, 1945. On his last visit to Cleveland, Kalish mentioned that he wanted his children born in the town that he and their mother considered their home. After his death in 1945, at the age of 54, the Cleveland Museum of Art gave a memorial exhibition of Kalish’s work jointly with the paintings of Alexander Warshawsky. From his student days in Cleveland, to his later years when he had won nationwide renown in his chosen field, the art of Max Kalish mirrored his interest in the life that surged around him. It was his ambition to tell in everlasting bronze or stone, the story of the American people and the great leaders who arose from their midst. He was tasked to portray the worker and to reveal the spirit of democracy and its influence upon the people. Many in the Cleveland community knew Max Kalish personally; future generations will know him through his works. ● |

||

|

|

||

|

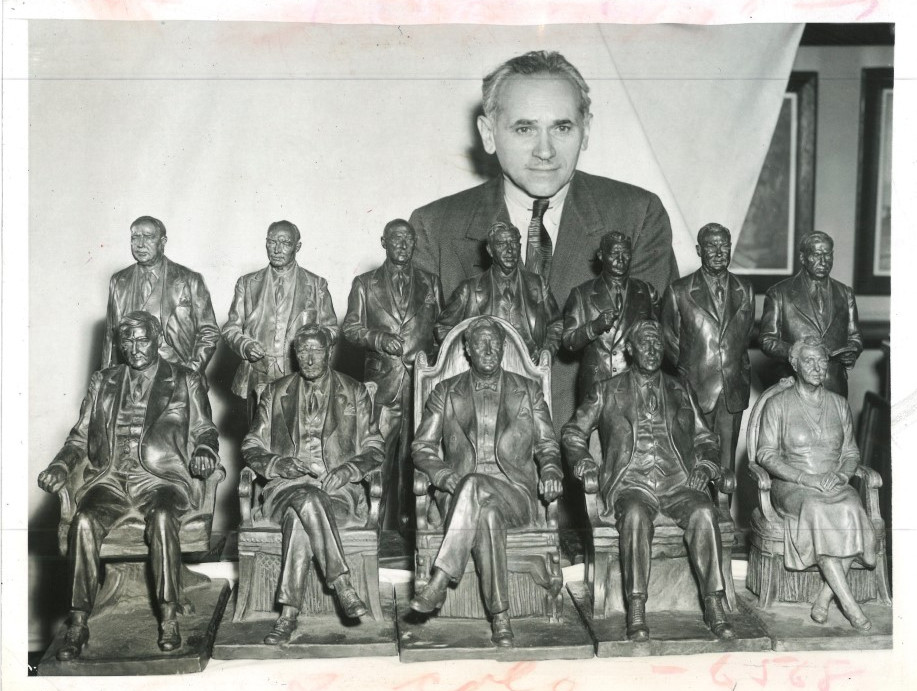

Sculptor Max Kalish in his Paris

studio working on the Lincoln statue - September 1928 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

"Kalachick's Best Work" Jewish Independent April 22, 1910 "First Prize in Sculpture Won by Max Kalish at Exhibit of Work of Cleveland Artists" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, May 09, 1924. "Max I Kalish Returns From Paris" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, January 23, 1925. "To Execute Lincoln Statue" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, April 08, 1927. Kelley, Grace V. “Art Notes” – Cleveland Plain Dealer, Sunday, April 17, 1927. “Kalish Statue of Lincoln Will Be Dedicated Today in Presence of Thousands of School Children Who Aided Move to Honor Emancipator” -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, February 12, 1932. “2,500 Pupils See Lincoln Statue on Mall Unveiled” – Cleveland Plain Dealer, Saturday, February 13, 1932. "Max Kalish to Reopen I Studio in Cleveland" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, May 13, 1938. "Max Kalish, Sculptor, Dies in N. Y. at 54" --The Jewish Review and Observer, Friday, March 23, 1945. "Max Kalish" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, March 23, 1945. "Joint Memorial Exhibition to Honor Late Max Kalish and Alexander Warshawsky at Cleveland Museum of Art" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, September 06, 1946. "Judas Maccabeus" -- The Jewish Independent, Friday, December 12, 1952.

"Max Kalish Remembered" -- Cleveland

Jewish News, Friday, November 28, 1969.

Learn

More About Max Kalish “Max Kalish.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. "Abraham Lincoln in Cleveland” Cleveland Historical "Cleveland's Jews Mourn Abraham Lincoln" Cleveland Jewish History

“Max Kalish”

Smithsonian American Art Museum. Acknowledgements

Arnold Berger, Editor and Webmaster,

ClevelandJewishHistory.net |

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Gail Greenberg, MSEd. is an educator and library media specialist whose teaching experience includes public and private Jewish day and community schools, adult education, and professional development seminars. Currently, she is an adjunct faculty member at Cleveland State University in the Office of Field Services, supervising pre-service teachers. She is also a volunteer docent at The Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage. She has published on Cleveland Historical. For her earlier contributions on this website see: “Building The Temple in University Circle” and “Glenville’s Morison Avenue Russian Turkish Bath House and Mikvah.” |