He was hired as a Melamed [teacher] to the children of Eliezer Rubinstein, who lived in the village of Harinich where he farmed fields and operated a mill leased from the local church. While in the country the young Zvi Hirsch took advantage of any books he could find to further his Jewish learning by studying the works of the medieval Jewish philosophers and to acquaint himself with European culture (he thus gained knowledge of literary Russian through a Russian translation of the Biblical book of Isaiah.) At the age of 18 he married Yetta, the eldest daughter of his employer, who was 15 years old at the time, and joined his father-in-law’s business. His longing for a more intellectual, city life persisted and was soon satisfied in an abrupt manner when the Russian government put an end to the family’s source of livelihood in the village as part of its policy denying Jews the right to lease Christian property. Zvi Hirsch, by then father to his oldest, Haim (Herman), made an attempt to engage in commerce in the nearby city of Pinsk. At that time the government-appointed Rabbi, A. H. Rosenberg, noticed the young man’s intellectual ability by sheer chance. Rosenberg gave Masliansky part time employment as a teacher in the modern Hebrew school he had established and arranged for private students to supplement his income. The family thus settled in Pinsk where four children – Bertha, Pinchas (Philip), Fruma Gittel (Fanny) and Hanna (Anna) were to be born. In spring 1881, following the wave of pogroms in southern Russia, a new phase in his life started. He joined the Hibbat Zion [Lovers of Zion] movement and preached its ideology of Jewish nationalism and the return to the Land of Israel, while maintaining his full schedule as a teacher. In 1884 the first universal fundraising drive of the movement took place – the selling of pictures of the benefactor Sir Moses Montefiore in honor of his hundredth birthday. Masliansky directed the appeal in Pinsk and enlisted his students to distribute the pictures. An exceptionally large number of pictures were allotted to his pupil, a student of the polytechnic institute, who also aided Masliansky in his administrative work on behalf of the movement: Chaim Weizmann. It is not surprising that many years later the President of the World Zionist Organization called Masliansky “my very first teacher in Zionism,” and added: “his speeches laid the foundation of my Zionist belief.” In 1888 he moved to Yekaterinoslav with his family, where the two youngest children, Batya (Beatrice) and Emmanuel (who was to die at the age of five) were born. He continued his work as Hebrew teacher and his activity and preaching on behalf of Hibbat Zion. Four years later the movement decided to send him on a tour of the various Jewish centers in Russia and Poland. His sermons, which combined some of the traditional techniques of the Jewish preacher (maggid or darshan) with more modern subjects and methods, gained great popularity and left a lasting impact on many listeners. They also raised the ire of the Russian authorities that harassed, imprisoned and expelled him from various towns and finally in 1895 ordered him to leave Russia. Following the recommendation of the leaders of Hibbat Zion he “went with the people” to America. His wife and six children (his eldest son Haim/Herman had already emigrated to America with his uncle, Abraham) soon joined him in New York, where he became a pivotal figure in Jewish life especially in the absorption of the mass immigration from Eastern Europe. He urged the immigrants to remain loyal to their Jewish tradition and at the same time adapt and integrate to life in America. He maintained that far from being incompatible these goals were actually complementary, as was the Jewish national idea: Masliansky, who was completely devoted to the ideal of American Freedom, could not conceive any inconsistency between it and the renewal of Jewish national life.

Masliansky furthered his message in three ways: in writing as

regular contributor to the Hebrew and Yiddish press, including the

brief publication of his own paper Die Yidishe Velt; through

communal activity and involvement in all national, Hebrew and

charitable enterprises (he served as Vice President of the American

Zionist Organization from 1901-1910); and most and foremost orally,

preaching his sermons from the pulpit. He spoke in practically every

city where there was a sizeable Jewish community, but his base for

nearly thirty years was the Educational Alliance in New York, that

remarkable pioneer “community center” established by philanthropic

Jews for the immigrant East Side. The great impression his sermons

made on the crowd is evident in the recollections of Abba Hillel

Silver who, when reading the sermons in print, wrote of the “glory

of…[Masliansky’s] eloquence,” and added: ”it was like hearing anew

the echoes of my youth. I could see you again, standing on the

platform of the Educational Alliance… pouring forth a brilliant

cascade of sparkling phrases, your wisdom and your inspiration. I

could see again the eager, tense faces of the thousands who listened

to you.” At the memorial service to Masliansky Silver further

described the audience as coming to hear him “with bleeding hearts

and parched lips.” Masliansky’s contribution to the immigrant generation in America was especially great. By greeting them in Ellis Island on Sunday and by delivering his sermons in their own language, he revived their national feelings and traditions and managed to bring them consolation at this difficult point in their lives, bridging the gap between the old world they had left behind and the new unknown world ahead. ●

|

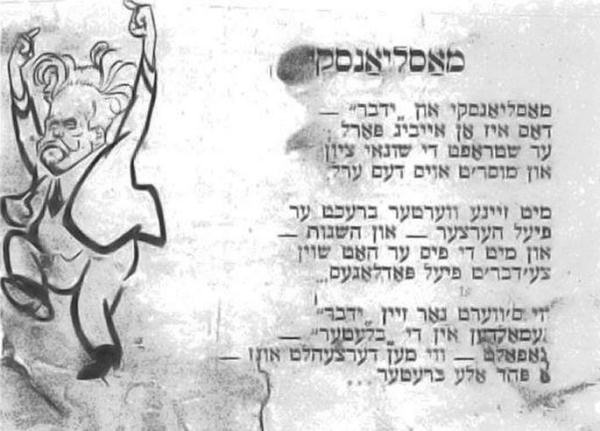

From a Google book on Jewish life in New York City. A YIVO publication shows a cartoon of Reverend Zvi Hirsch Masliansky in the height of oratorical fervor and a poem in Yiddish. Thanks to Zviah Nardi and Judith Weiss with the help of Joe Wernik for this translation. His speeches were often announced as "Masliansky Yidabber" (Masliansky will speak.)

|