|

|

Cleveland and the Freeing of Soviet Jewry | |

|

Involvement in the Soviet Jewry

Movement

—

by Louis Rosenblum |

||

|

Project Sefer This project addressed the needs of Soviet Jews intent on learning

Hebrew. Resurgence of interest

in Hebrew was two fold. First, it was a connection with ones Jewish

roots — Hebrew is the

language of Jewish liturgy and the Bible. Second, for those whose

goal was aliyah (immigration

to Israel), fluency in Hebrew would speed integration into Israeli

society. Beginning in the late

1960s, non-official groups were formed and classes held in private

homes. I became aware of

this activity in 1971, in telephone conversations with Soviet Jewish

activists. Subsequently,

Project Sefer was set up to meet the various needs of the Hebrew

learning groups throughout

the Soviet Union.

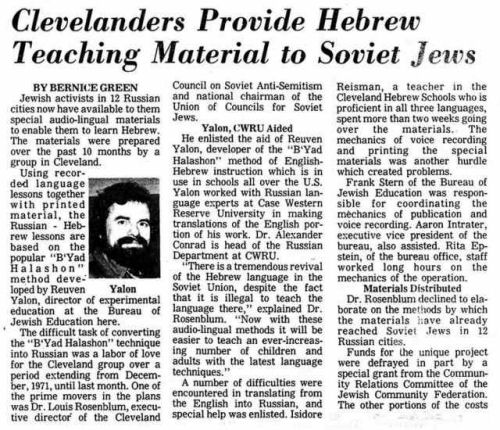

Top on the needs list were textbooks for all student levels. A people-to- people mass mailing of books started in 1973 and continued through 1977. Our Israeli partner and advisor in this endeavor was a group of former Soviet Hebrew teachers lead by Moshe Palchan (and later by his brother Israel). This group, Association for the Dissemination of the Hebrew Language in the USSR העבר”מ , also posted books from Israel. By the most important measure of all, our combined effort was a resounding success. Michael Goldblat, a Hebrew teacher in Moscow during the entire period of the mailings, wrote, “The number of books that you have sent us was the critical element — the keystone — in the development of the Hebrew language in Moscow.” Lastly, I want to mention two special undertakings that peculiarly benefited from the talents and enthusiasm of Cleveland Jewish educators and institutions. The first enterprise, begun in December 1971, in association with Reuven Yalon of the Cleveland Bureau of Jewish Education (CBJE), was the preparation of special recorded language tapes and material for the self-study of Hebrew for Russian speakers. Other individuals also volunteered their help: Dr. Alexander Conrad, head of the Russian Department at Case Western Reserve University; Isadore Reisman, of the Cleveland Hebrew Schools; and Aaron Intrater, Rita Epstein and Frank Stern of the CBJE. The CJCF provided a grant to defray part of the material expenses not covered by the CCSA. Ten months later, the job was completed and I arranged for copies of the tapes and an associated study book to be channeled to Hebrew study groups in 12 cities in the USSR.

The second of the special undertakings was in direct support of the

teachers. Soviet authorities long

regarded the study of Hebrew with great suspicion — teachers were

harassed and Hebrew books

confiscated. When this failed to dampen Hebrew language studies, the

government announced that

teaching without certification was illegal.

Travel arrangements were made. (Henry decided to take his college-aged son, Jed, along for support and companionship.) Well beforehand, I informed my contacts in Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev of his schedule. Expenses for the trip were covered by the CCSA. In June, Henry spent two-week in the Soviet Union, met productively with many teachers and students, and tested and certified 32 teachers in all. For more on the mission of Henry Margolis, click here. [pdf] |

|

|

| © 2007 Louis Rosenblum |